Balanus nubilus (Arthropoda, Crustacea, Thecostraca, Cirripedia, Thoracica, Sessilia)

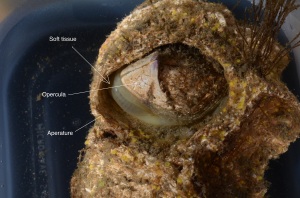

The giant barnacle, Balanus nubilus, is a sessile organism that attaches itself on a chosen substrate and remains there for the duration of the organism’s lifespan (Figure 1). They do not leave their shell, yet open it up for life functions such as: feeding, spawning, and respiration. They are suspension feeding animals that use their feet to extract food from the water column. My observations are based upon organisms with apertures or openings that are around 4cm in length. The giant barnacle has long and short cirripedia showing a clear distinction between the two (Figure 2). Under the short cirri are feeding appendages composed of maxillae and a mandible, which looks very sturdy in comparison to the cirri (Figure 3).

When feeding, the giant barnacle first opens its operculum and then extends and uncurls its cirripedia into the water column (Figure 4). The cirri still retain a slight curve when fully extended into the water column. I found when orienting the water flow from the sea table in the test barnacles direction, verses turing the water flow off, the feeding rate changed. The giant barnacle extends its cirri more frequently when there is less water movement. This appears to increase the water flow around the cirri and helps the barnacle to feed more efficiently. When there is ample water flow, barnacles seem to keep their cirri extended into the water column for longer periods, therefore beating them less frequently. The cirripedia can be swiveled to either side once extended (Figure 5). This action seems to better orient the cirri and face into the current’s flow. Smaller barnacles species feed more rapidly than larger barnacle species. They frequently extend their cirri at a rate of more than once per second whereas larger barnacles beat their cirri at a slower rate.

Barnacles are likely to stop feeding and narrow the operculum if they sense a predator above them. They seem to most likely sense predators by an interruption of light and shadows being cast over them. An agitated barnacle is timid to readily feed again and may cautiously take many minutes to resume feeding activity.

If a barnacle is poked along the soft tissue under the edge of the operculum, it swivels its operculum around the aperture in order to hide the soft and vulnerable tissue from a predator (Figure 6). On large barnacles this sometimes means they expose a vulnerable area of soft tissue on the other side of their opercula. The swiveling movement seems very quick for such a large barnacle.

Bailey Navratil

University of Washington