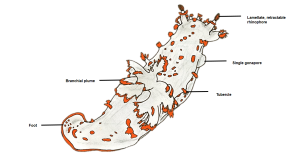

The docks of Friday Harbor Laboratories (Friday Harbor, WA) provide an excellent collection site for a host of subtidal marine invertebrates; arguably the most striking of these is the dorid nudibranch Triopha catalinae (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Diagram of T. catalinae (dorsal view) with major anatomical features labeled. Note that in nudibranchs, the mantle comprises the soft dorsum

During an attempt to record feeding preference data for this taxon, three individuals were collected from the docks in June of 2013, and a fourth was acquired from the lab of Dr. James Murray (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Photo of all four T. catalinae individuals used in the experiments consuming various bryozoans, including Dendrobeania sp. and Bugula sp.

These individuals were contained within a flow tank separated from other macro-invertebrates but could not be successfully segregated from one another. The movements and behavior of T. catalinae were recorded via real-time and time lapse video. Although little semi-quantitative data was gathered during this experiment, many observations were made with respect to their general behavior, and feeding habits in captivity (Table 1).

The first T. catalinae individual collected was habituated for approximately two weeks prior to the introduction of the others. Initially, it was contained within a flow tank shared with other dorids, a single aeolid, Hermissenda crassicornis, and multiple arthropods. It became necessary to remove the arthropod fauna as shrimp of the genera Pandalus and Lebbeus were observed surrounding T. catalinae in what appeared to be stalking behavior. As a result, these animals were put into “arthropod hell” where they likely ate one another; however, this cannot be confirmed… Despite this trauma, T. catalinae became increasingly domesticated and began accepting food directly from the hand of this worker providing the only record of such behavior in this taxon (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3zaN80kSI58&feature=youtu.be). Furthermore, each individual exhibited an initial reaction to touch that involved the retraction of their rhinophores, and general flattening of the dorsum; this behavior appears to be directly related to stress as it was also observed in individuals who came under other stresses (e.g., getting their head stuck in the outflow tube). After some time, the stress response subsided when T. catalinae was handled by this worker. Notably, all T. catalinae individuals within this experiment exhibited similarly domesticated behavior to the first with the exception of allowing hand-feeding.

McDonald and Nybakken (1996) provide a review of known prey items of T. catalinae, which suggests that this taxon is not highly specialized in their feeding habits. Individuals from Friday Harbor were provided with Bugula sp,, Dendrobeania sp., and a demosponge. From the little data collected as well as observations made over the five-week experiment, it appears that T. catalinae prefer Dendrobeania sp. and Bugula sp.. However, this information is largely anecdotal, and more work is required to constrain the feeding preferences of these animals should any exist. In particular, the lack of separation and frequent mating between all individuals may have biased the results (i.e., larger individuals may exhibit different food preferences as may those releasing egg masses). As noted by Cowles (2007), T. catalinae mate readily in captivity, and this was observed multiple times by this worker and other more disturbed onlookers.

It is surprising how little in known regarding the behavior and ecology of this common and distinctive nudibranch. Most work conducted on T. catalinae has focused on their defensive biochemistry; over five weeks, I attempted to gather behavioral and food preference data that might assist in a better understanding of these animals. While I was unsuccessful in testing their food preferences, I report here the potential for domestic behavior as well as the necessity for separating individuals in further experiments as both mating and body size differences possibly biased the data.

Tristan Betzner

University of Colorado

References:

Cowles, D. (2007). Triopha catalinae. http://www.wallawalla.edu/academics/departments/biology/rosario/inverts/Mollusca/Gastropoda/Opisthobranchia/Nudibranchia/Doridacea/Triopha_Catalinae.html.

McDonald, G. R., & Nybakken, J. W. (1996). A list of the worldwide food habits of nudibranchs. Online article: http://people. ucsc. edu/~ mcduck/nudifood. htm.

With special thanks to my patient professors, Bernadette and Gustave, the TA who saved the day: Kevin, Jim, Rhi, Nadia, Craig, everyone else who made my foray into “nudibranch-land” possible, and most especially, Triopha, for captivating my imagination and eating bryozoans out of my hand.