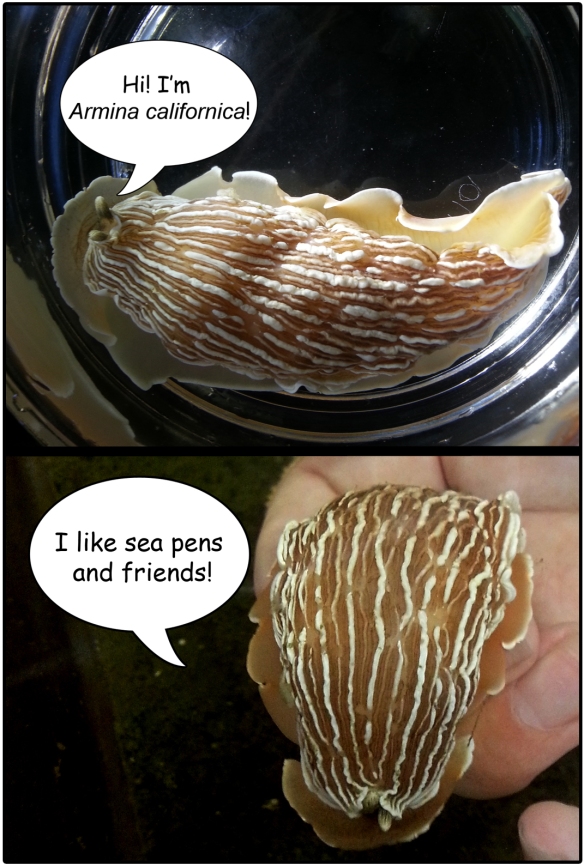

Meet Armina californica:

If the nudibranch world was a high school, the arminids would be the misfits. With their distinct lack of frills and gills and unique lifestyle, they don’t blend in with any other clique—the fancy aeolids, the sweet dorids (don’t even get me started on those sea-huggin’ dendronotids). However, the arminids don’t seem to mind the exclusion. Measuring up to around 10 cm in length, these sand-cruisin’ sea slugs can easily chomp away on a sea pen alone; but they are often found clustering together sharing a yummy Ptilosarcus meal.

It’s not only their peculiar appearance that sets them apart; their eccentricity runs much deeper than mere physical characteristics. The bauplan of A. californica seems exceedingly simple and inconspicuous, but the internal features make biologists scratch their heads.

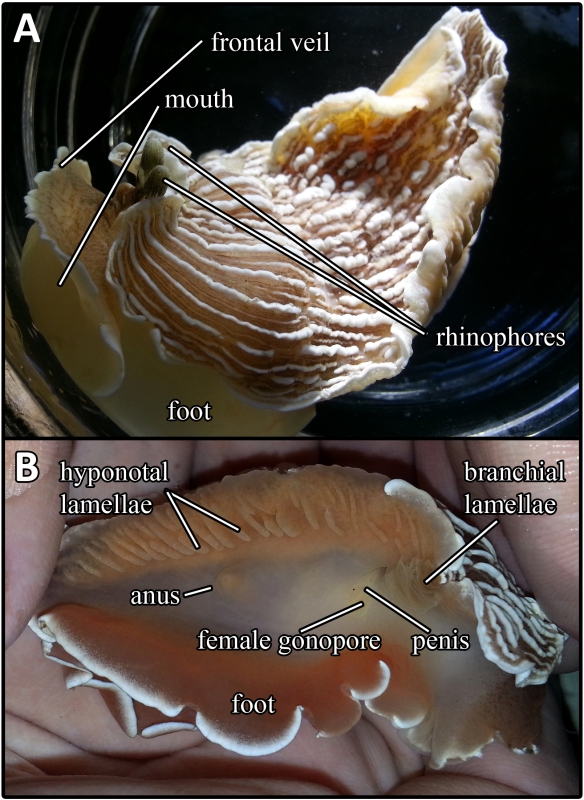

External Anatomy

The body of A. californica is typically grayish-pink in color with white peripheral margins and meridional ridges. The striated bulbous rhinophores protrude tightly from a small notch at the anterior dorsum. Unlike the aeolids and dendronotids which have respiratory structures within their cerata and the dorids which have distinctive branchial plumes, the arminids do not possess obvious gills. Instead, the strategy involves sets of lamellae that act as respiratory structures (branchial and hyponotal lamellae) located on the underside of the dorsal flaps. The right side of the foot contains both the anal opening and a gonopore complex that is host to both the female opening and the penis. On the ventral side, the foot extends laterally beyond the edges of the dorsum and anteriorly into a veil-like structure covering the mouth. This gives the animal an overall two-tiered structure.

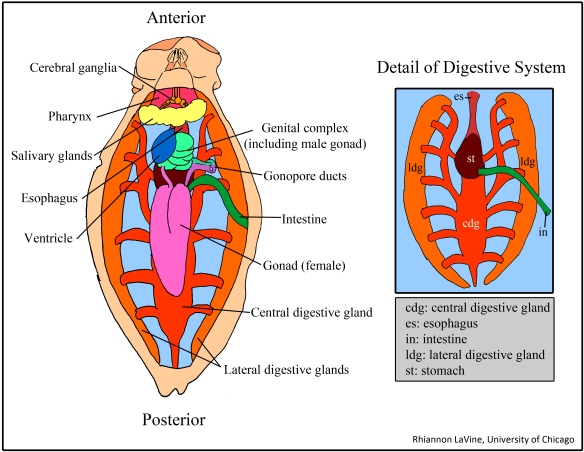

Internal Anatomy

The dissection of this animal is performed as a simple longitudinal incision of the dorsal surface. The most striking aspect of the internal structures may be the fact that many organs, including the cerebral ganglia, are colored bright orange due to the abundance of carotenoids from the armind’s diet of Ptilosarcus. At the most anterior end, the bright orange 4-ganglia brain sits atop the buccal mass (which contains the pharynx, radular sac, and all related mouthparts). Moving posteriorly, the salivary gland mass conceals the esophagus and its connection to the stomach. A bundle of organs that lies behind the salivary gland includes a clear ventricle and the genital complex—a set of glands and structures that aid in reproduction in addition to the male gonad. Connected to the genital complex is a large, orange gonad which houses the female reproductive components. Both the female gonad and the genital complex are connected via a paired gonoduct to the exterior gonopore complex.

The digestive system includes the anteriormost esophagus which leads directly into the stomach. The stomach extends uninterrupted into the central digestive gland forming one large continuous structure from which emerges the intestine. The branches of the central digestive gland connect back to the stomach, and to a pair of large, orange, lateral digestive glands, the function of which is as of yet unclear and makes this organism quite peculiar. It has been suggested that these glands play a role in the processing of the A. californicus’s odd diet of sea pens, a prey item that can fight back with stinging cells known as nematocytes. Much to the sea pen’s dismay, the arminid seems immune to its venom. The placement of the lateral digestive glands on the body wall may also hint at a further function: are these organs somehow retaining the nematocysts? Perhaps this foreshadows a reuse-recycle defense mechanism similar to that of other gastropods that feed upon cnidarians. The idea is definitely some some food for thought when considering these eccentric bumblers of the sea.

Rhi LaVine

University of Chicago