The first worm that comes to peoples’ minds is often the earthworm. Unknown to many non-biologist and marine scientists (and non-worm enthusiasts), the oceans are teeming with a diversity of worms and some of these worms are the most curious and beautifully colored inhabitants of the marine world.

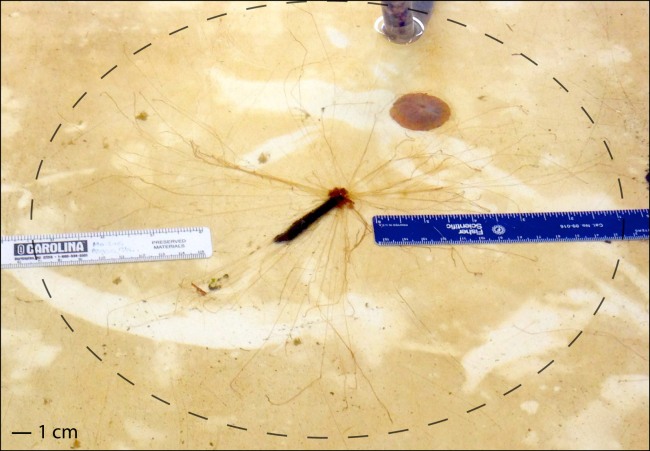

A spectacular group of these animals are the spaghetti worms of the family Terebellidae. True to their name, these worms appear to be a splay of spaghetti noodles on the seafloor. Terebellids live in tubes or burrows on the seafloor and spread their spaghetti-like tentacles (palps) across the sediment surface from the opening of their tube. A terebellid of approximately 6 cm can have dozens of tentacles over 15 cm long (Figure 1). Each tentacle has a longitudinal central groove lined with cilia. The tentacles feel the seafloor for materials that will help construct a sturdy tube or burrow, such as shell fragments, small rocks, and mud that stick to their body with a secreted mucus. Tentacles also search surface sediment for tasty organic matter. The worms bring particles and food back to the burrow via the cilia in a manner similar to a conveyor belt.

Figure 1. Terebellid with tentacles extending 360° about its body. Dashed ellipse outlines the extent of the tentacles’ reach. The tentacles spread covers approximately 518 cm2, estimating the radii of the ellipse is 15 cm and 11 cm. The body length of the terebellid is 6 cm, not including the tentacles or fire red branching gills.

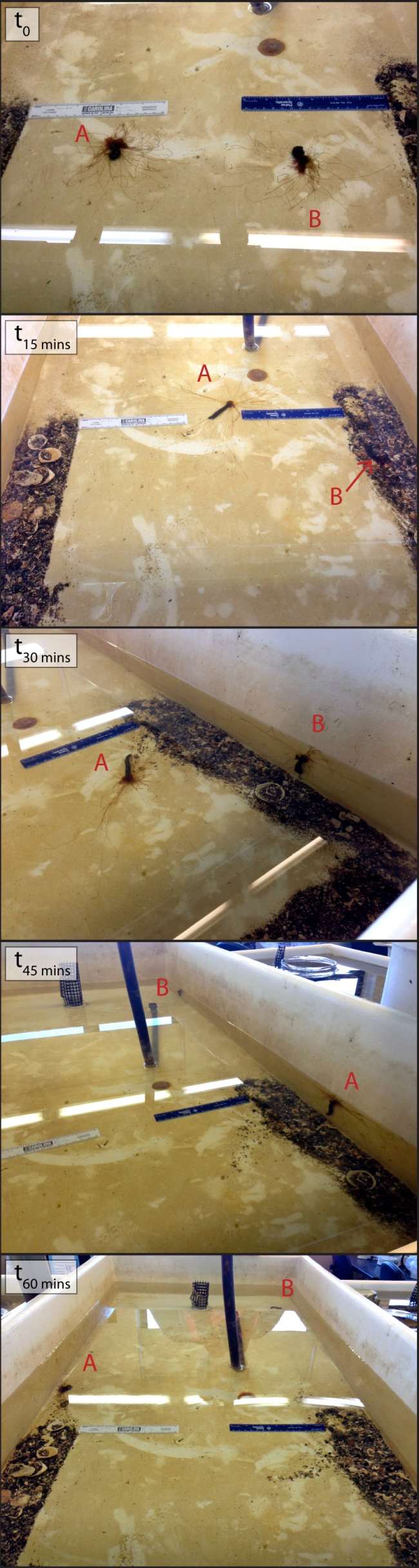

Because the tentacles serve these two purposes, I tested the hypothesis that terebellids will preferentially extend tentacles and move their body toward sediment rich in nutrients or materials useful in the construction of their tubes. To test this hypothesis, I placed two individuals of the species Eupolymnia heterobranchia, collected from Argyle Lagoon, San Juan Island, WA, in a sea table cleaned of debris, sediment, and other organisms (with the exception of a persistent sea anemone). At one end of the table, I lined the walls with a boarder of sediment, approximately 7 cm wide. The worms were removed from their self-constructed mud tubes and placed naked in the sea table. Each spaghetti worm was positioned to face their own sediment wall at a distance of 10 cm (Figure 2).

I observed the worms every 15 minutes for an hour and both of the worms’ movements about the sea table were random. Neither worm transported sediment along their tentacles for feeding or to construct a new body tube during the period of observation. Moreover, the tentacles did not extend in a preferential direction toward sediment; instead tentacles surrounded the body in 360° (Figure 1). Potential reasons for the lack of interest in the sediment include: sediment did not suit the habitat type of the worms, animals were in shock after being stripped of their outer tubes, and/or no predators were present in the sea table to encourage the worms to build tubes. Although I observed no particle transport along the tentacles, these two terebellids did show an unexpected amount of movement (~2 cm/min) about the sea table for being tube/burrow dwellers (Figure 2). However, it remains unclear if this movement was via cilia or body contractions.

Figure 2. Photos of the two terebellids (A & B) in the sea table experimental set-up at their initial placement and for each sequential 15 minutes for the following hour: t0, t15, t30, t45, and t60 (top to bottom). The dimensions of the sea table are 60 cm wide by 120 cm long. The blue and white rulers are both 15 cm for scale. Note the distance covered by these worms in the span of 1 hour: estimated average velocity for these two terebellids is 1.9 cm/min, ranging between 0.5 – 6.0 cm/min.

Caitlin Keating-Bitonti, Stanford University